seizures, spinal fracture, back pain, trauma, diagnosis

Epilepsy is a chronic neurological disorder characterized by sporadic and mostly unpredictable epileptic seizures affecting about 50 million people worldwide [1]. Fractures and dislocations associated with convulsive events have been described mostly in case reports with low-level evidence. Seizures mainly induce fractures of the humerus, scapula, hip, and spine. It was shown that the incidence of fractures after seizures is 0.3%, and the incidence of spinal fractures induced by seizures is 0.04% [2].

Current literature lack information regarding bone fractures in epileptic patients. There is no protocol for orthopedic evaluation for skeletal injuries following an epileptic attack. These injuries are often missed or diagnosed in a delay due to the absence of physical signs and other pressing symptoms and may result in serious neurological deficits [3]. Convulsive events may be accompanied by audible cracking and result in back pain. In those cases, prompt clinical and imaging evaluation is required [4]. Neurological consequences may be hazardous, from acute foot drop to tetraplegia [5, 6].

Fractures can occur either directly as a result of the violent force of a seizure or may occur secondary to falling at the time of the episode. In the absence of external trauma, it is suggested that the mechanism of vertebral fracture is the powerful contraction of the paraspinal muscles during a seizure [3]. Due to a similar type of fall mechanism, fracture patterns associated with seizures or a syncope seem to be comparable [1].

Chronic use of antiepileptic drugs (phenytoin, phenobarbital, carbamazepine, valproate) is recognized as a cause of secondary osteoporosis and may predispose to vertebral compression fractures [7]. The most common type of fractures is A1 and A4. Seizure-Induced Spinal Fracture (SISF) may be observed on any level of the spine, with L1 and L2 as the most common sites of injury [2].

A 30-year-old patient arrived at the emergency room following a tonic-clonic epileptic seizure. The patient suffered from tonic-clonic seizures during his childhood and was treated with Depalept, however, at present was not under any antiepileptic medication. Other than that, he had no medical history. More than 20 years have passed since his last epileptic seizure. He has not been under neurological follow-up, and there was no data regarding his neurological condition.

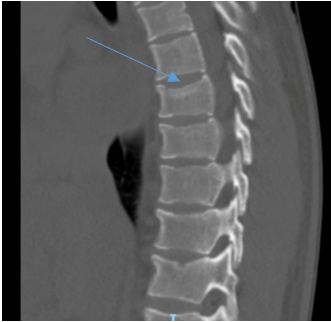

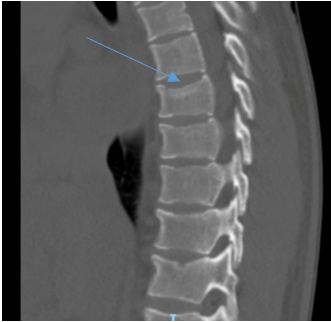

The attack happened at work. He reported that previously to the attack he felt well. His colleagues witnessed the attack and reported a loss of consciousness and jerky movements of his limbs for 4 minutes that stopped spontaneously. In the postictal period, he felt sleepy but had no neurological deficits. He was referred to hospitalization for observation and further investigation. The next day he reported persistent back pain at the level of the mid-thorax region. He had no signs of trauma on his skin. Plain radiographs of the thoracic spine demonstrated a collapse of the superior endplate of the vertebral body of D7 (Figure 1). The patient underwent a CT examination that confirmed the diagnosis of compression fracture of the upper endplate of vertebrae D7 (Figure 2).

The patient suffered from another similar attack one month later including loss of consciousness and eye-rolling. New radiographs of the vertebral spine showed worsening of the collapse of vertebral body D7 and a new fracture of vertebral body D8 (Figure 3). CT confirmed the diagnosis of an adjacent compression fracture of vertebra D8 (Figures 4 and 5).

Figure 1: Plain radiographs demonstrate the collapse of the superior endplate of D7.

Figure 1: Plain radiographs demonstrate the collapse of the superior endplate of D7.

Figure 2: Compression fracture of the upper endplate of vertebrae D7 demonstrated on a CT scan.

Figure 3: New radiographs reveal another fracture of the adjacent vertebrae D8.

Figure 4: Sagittal and coronal CT scan views exhibit adjacent compression fractures of D7 and D8 vertebrae.

Figure 5: Sagittal and coronal CT scan views exhibit adjacent compression fractures of D7 and D8 vertebrae.

Fracture is rarely associated with an epileptic episode. The mechanism of injury may be non-traumatic. The asymptomatic period is typical due to a cloudy sensorium in the postictal phase. The diagnosis of fracture injury may be delayed by up to a few days in some cases. The most common musculoskeletal injuries include spinal compression fractures as well as shoulder fractures/dislocation injuries, manubriosternal joint disruption, and dental injuries.

The spine is a common seizure-related fracture site and may be associated with hazardous neurological deficits. Compression fractures occur more commonly than burst fractures. The mechanism of injury of compression fractures may be non-traumatic, referring to abdominal and paraspinal muscle forceful spasms. Mostly no acute specific complaints are presented by the patients, nor any major neurological sequelae. Injuries involve the mid-thoracic spine, where the compression forces concentrate along the anterior and middle thoracic kyphotic spine [8].

Our patient had a convulsive attack and did not present any specific complaints. Days after the injury, he reported back pain. The diagnosis was delayed a few days from the moment of injury. There was no description of direct trauma by witnesses, and anamnesis was very limited due to the postictal state. Careful attention and suspicion are required to diagnose orthopedic injuries in those patients. The next convulsive episode resulted in a similar compression fracture to the consecutive thoracic vertebra, implying that those fractures are highly associated and may even be defined as pathognomonic with seizure. Appropriately addressing the underlying risk factors for seizure-induced pathological fractures might be helpful in preventing them in the future. The role of imaging in the diagnosis of fracture injuries is very critical.

![]() *, Halaika M and Yassin M

*, Halaika M and Yassin M![]()